🇨🇳 This edition of Drift Signal examines China's transformation into the world's advanced manufacturing powerhouse, and what it means for global technological leadership. I trace the journey from Deng Xiaoping's reforms to today's AI-powered factories, exploring how China evolved from simple low-cost assembly to mastering advanced manufacturing at the intersection of hardware and software.

This is a long read, but the stakes are significant: Which nation will lead in creating value in the 21st century? Where will the resulting wealth be converted into military power and strategic influence? And how should the West position itself in this shifting landscape?

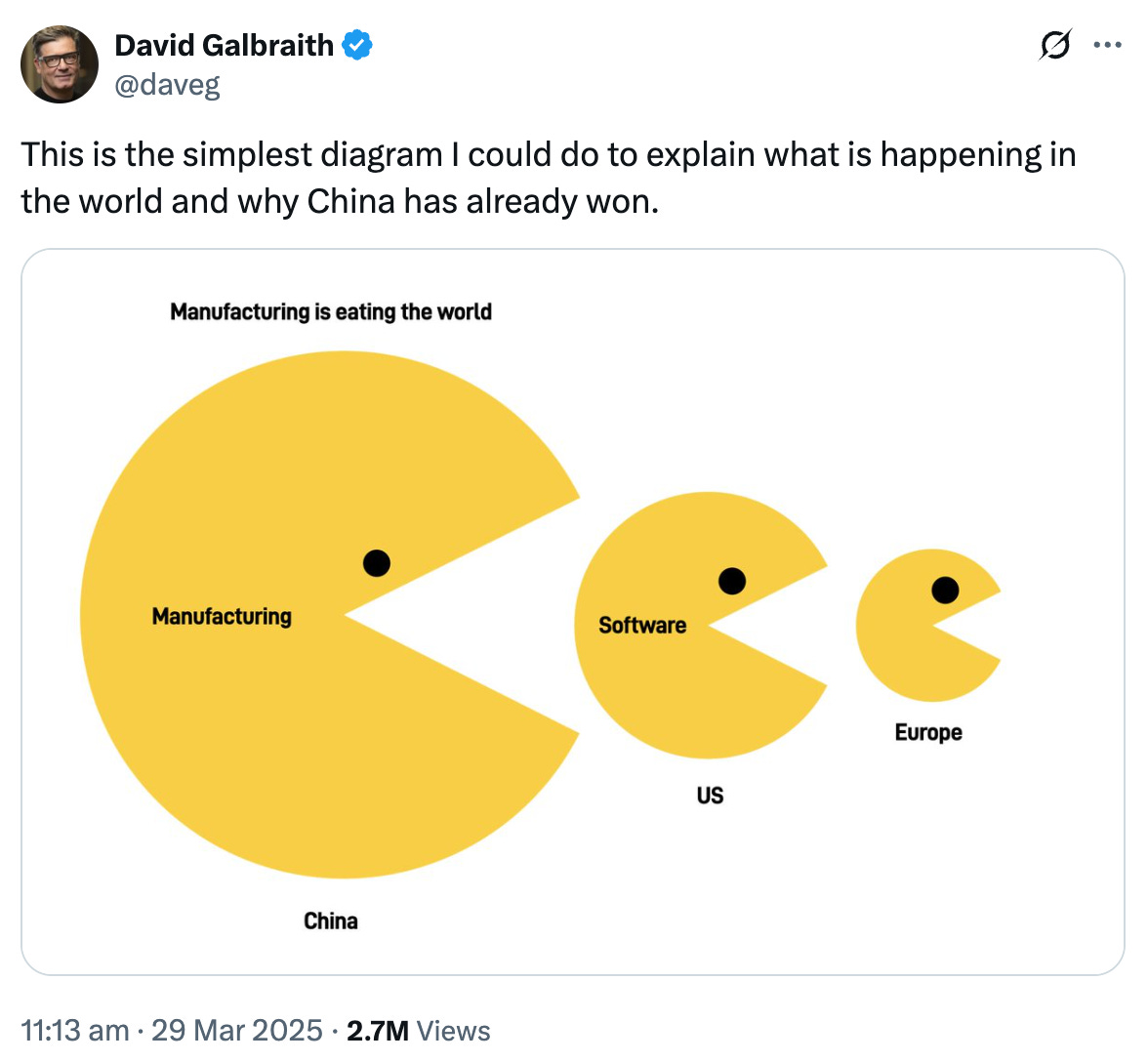

Special thanks to Nick Denton, who recently shared his bullish thesis on China during a recent edition of Bloomberg’s “Odd Lots” podcast, and to David Galbraith, whose inspiring thread on X helped crystallise several key ideas explored here.

Pour yourself a cup of something and settle in 👇 Here’s the outline:

Is this the Chinese Century? Examining China's staggering manufacturing numbers and the deeper questions they raise about future global leadership

What was China before it became a factory? Pre-reform Communist China and the foundations that enabled its transformation

How did Deng change the game? The critical reforms and strategies that launched China's economic rise

Is copying the real secret to success? How China mastered imitation-driven innovation as a launchpad for manufacturing dominance

Beyond cheap labour: what's China's true advantage? Understanding the depth of manufacturing expertise and process knowledge China has developed

Does manufacturing explain Xi's Chinese tech crackdown? How China's pivot from consumer tech to advanced manufacturing reflects strategic priorities

Is manufacturing eating the world now? The fusion of hardware and software at industrial scale and China's position at this intersection

Is the West becoming the new developing economy? The uncomfortable parallel of role reversal and the West's struggle to catch up

Is America abandoning both ends of the market at once? How US policy undermines both traditional manufacturing and high-end activities

Where do we fit in the Chinese Century? Future scenarios and how the West might position itself in a China-dominated industrial landscape

1/ Is this the Chinese Century?

It’s clear that Donald Trump has lost the PR war, maybe even the economic one, following the escalation of his tariff-driven trade conflict.

His recent proposals for unprecedented tariffs on Chinese imports have prompted a fresh wave of analysis about manufacturing competitiveness. You can see it in the sudden wave of articles and podcasts highlighting China's manufacturing dominance, and in the West's mounting concern about its implications for the global order. Noah Smith has even suggested that we may be entering the “Chinese Century”, adding that it isn't necessarily a good thing.

As always with China, the numbers are staggering: a population of 1.41 billion; 29% of the world's manufacturing output; and a GDP on track to surpass that of the US. China produces more than half of the world's steel, 60% of its electric vehicles, and dominates battery production and solar panel manufacturing. Its port infrastructure handles more cargo than the next five largest ports combined, and it builds more high-speed rail each year than the rest of the world put together. Even individual companies have reached unprecedented scale: BYD, the electric vehicle giant, now employs over 900,000 people and outsells Tesla globally; while drone manufacturer DJI controls 77% of the global consumer drone market, with its products ubiquitous from Hollywood sets to construction sites.

But beyond these headline figures, this moment invites deeper questions: which nation will lead in creating value in the 21st century? Where will that value be converted into wealth? How will that wealth be reinvested in military power? And how much of that will translate into strategic influence? In essence, who will shape the next global order?

This has sparked a wave of soul-searching in the West. Can the US and Europe reverse the trend? Should we bring manufacturing home? Could we? How do we position ourselves amid a shifting trade landscape—and can China’s momentum be checked?

To answer these questions, we must understand what manufacturing has become. The assembly lines that powered the 20th century have given way to advanced manufacturing—where automation, robotics, AI systems, and smart materials converge. This isn't just about making things; it's about embedding intelligence into production itself. China's real achievement isn't just mastering traditional manufacturing, but leading in this fusion of software and hardware at industrial scale.

To understand this transformation, we need to look back. This essay revisits how China came to outmanufacture the West—not to romanticise its rise, but to examine what was done right, what went wrong, and what lessons we might adapt to our own context, in the spirit of Robyn Klingler-Vidra’s “contextual rationality”. The goal is simple: to think clearly about what comes next. Let’s start from the beginning.

2/ What was China before it became a factory?

The common narrative of China’s economic history often goes something like this: China, once a great civilisation, rivalled Europe in scientific and economic achievement; then the Ming dynasty turned inward, triggering decline; the West arrived with gunboats and opium; civil war followed; the People's Republic of China emerged in 1949; Mao’s tyrannical rule led to stagnation; Nixon and Kissinger reopened relations; Deng Xiaoping unlocked growth through cheap labour and stolen know-how; and then China joined the WTO, exploited Western naïveté, and took over the world.

That story contains some truth, but misses much of the nuance. Rather than retracing every step, let’s begin with a simpler premise: very little entrepreneurial or industrial progress occurred in pre-reform Communist China. Before 1978, the country bore little resemblance to the manufacturing giant it would later become. It was predominantly agrarian, with limited industrial infrastructure. Political upheaval following the Communist victory in 1949—and Mao Zedong’s ideological campaigns—badly hampered development.

Under Mao, China followed a Marxist model of centralised planning. The state controlled production, and industry was geared towards self-sufficiency and heavy manufacturing, not consumer markets—closely echoing the Soviet approach. The Cultural Revolution further paralysed progress, as dogma supplanted pragmatism and millions were persecuted.

Then something shifted—but it wasn’t inevitable, and it certainly wasn’t immediate.

First, contrary to popular belief, China’s economic opening wasn’t triggered by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. While Nixon’s 1972 visit marked a geopolitical turning point, it had limited economic impact at the time. Mao remained firmly in charge, and rather than embracing reform, he marginalised Premier Zhou Enlai and his pragmatic allies—including Deng Xiaoping. (Deng had been Zhou’s protégé, and the two had even studied together in France in the 1920s.)

Second, China didn’t need World Trade Organisation (WTO) membership to become an export powerhouse. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, it enjoyed Most Favoured Nation trading status with the US from 1980 onward, allowing its goods to enter American markets at low tariffs well before its formal accession to the WTO in 2001. The transformation was already underway by then.

Third, what Deng accomplished after becoming paramount leader in 1978 was far from simple. His reforms risked instability. He personally ordered the crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, fearing that political liberalisation would undermine economic reform. Yet in 1992, during his Southern Tour, he acted decisively to prevent a deeper political backlash against business and reform, carefully balancing authoritarian control with a continued commitment to opening up the economy.

Overall, Deng’s balanced approach succeeded not through sudden liberalisation, but through careful, incremental policy shifts grounded in experimentation, a mindset Kissinger once remarked on with admiration:

Americans think a stable world is normal... If there’s a problem, you solve it, and move on. Chinese leaders think resolution of a problem is an admission ticket to another problem. So almost every Chinese leader I’ve met has viewed policy conceptually, as a process rather than a programme.

That mindset, coupled with Deng’s well-known doctrine of “hide your strength, bide your time” (韬光养晦, tāo guāng yǎng huì), laid the foundations for China’s transformation.

When Mao died in 1976, China was at a crossroads. With a population nearing one billion—just before the one-child policy was introduced—it had immense human potential but remained economically stagnant, technologically backward, and largely disconnected from global markets. It would take Deng’s return to power in 1978 to steer the country in a new direction and set it on the path to becoming the world’s factory.

3/ How did Deng change the game?

When Deng Xiaoping returned to power in 1978, he inherited a stagnant, inefficient economy largely cut off from global markets. Though he held no top formal title, Deng quickly emerged as China’s paramount leader, ushering in a new era of pragmatic reform. His philosophy was famously summed up in the phrase: “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.”

What Deng and the CCP accomplished then was nothing short of extraordinary. Their transformation closely followed the playbook Joe Studwell outlines in How Asia Works, which documents how Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China all drove growth through three coordinated steps: land reform, outward-looking industrialisation under strict “export discipline”, and financial repression—meaning the state directed domestic savings toward investment in strategic sectors.

Remarkably, the CCP applied each of these with precision, fuelling the fastest large-scale economic transformation in history. In 1978, China's GDP per capita was about $1,600 when adjusted for local purchasing power in today's US dollars—that is, what that income could actually buy within China. By 2012, it had risen to over $11,000. In just over thirty years, the average Chinese citizen had become seven times better off.

Land reform came in two waves. The first followed the CCP’s 1949 victory and involved radical collectivisation after the expropriation of landlords. But productivity remained low. The second wave, launched under Deng in the late 1970s, introduced the household responsibility system, which allowed families to lease land from the state and farm it independently. While the land remained collectively owned, individual households could now profit from surplus production.

This change had two major effects:

First, it significantly boosted agricultural yields. Families now had a direct incentive to maximise output, and although productivity per worker remained low—since entire families were labouring on relatively small plots—output per hectare surged. This not only secured the nation’s food supply but also gradually freed up labour for future industrial use.

Second, giving rural families control over their land helped prevent the kind of mass urban migration that overwhelmed other developing countries. In places like Manila, landless farmers flooded into cities, straining infrastructure and forming vast slums. In China, a more stable rural population gave cities time to build the capacity to absorb workers gradually.

The hukou household registration system reinforced this. It tied people to their place of birth unless granted formal permission to move—limiting internal migration. Though later softened and often criticised, it helped avoid the urban chaos seen elsewhere during early industrialisation.

Meanwhile, the CCP began developing an export-led manufacturing sector. Deng launched Special Economic Zones (SEZs), starting with Shenzhen—a fishing village just across the border from then-British-controlled Hong Kong. These zones allowed foreign investment, offered tax incentives, and gave local authorities more flexibility. They were designed to test market reforms without threatening national stability.

And, as already mentioned, in 1980, China secured Most Favoured Nation trading status with the US, ensuring low tariffs on Chinese exports. This gave Chinese firms access to Western consumers and imposed what Studwell calls “export discipline”: the pressure to meet global standards, which forces firms to become more competitive and efficient.

All in all, Deng never pursued shock therapy. Instead, he maintained the CCP’s tight political control while introducing market reforms step by step. China’s rise rested on three key ingredients: the political will to carry out long-term, disciplined development (“a process rather than a program”, to quote Kissinger again); a vast supply of low-cost labour; and an entrepreneurial culture that, despite years of suppression, had not disappeared. As Wenzhou pioneer entrepreneur Xu Yunxu once said: “It is said that people born here are born businessmen.”

By the 1990s, China’s industrial foundation was firmly in place. Agricultural reform had ensured food security and improved rural incomes. SEZs—first in Shenzhen, then in Pudong (Shanghai)—proved that controlled market liberalisation could succeed under a socialist framework. A new generation of entrepreneurs was learning to operate within a hybrid model that combined strong state oversight with opportunities for private initiative.

And of course, alongside broader reforms, China tightly controlled its currency, the renminbi, keeping it undervalued to boost export competitiveness. This exchange rate policy was another key instrument in the CCP’s comprehensive industrial strategy.

Overall, Deng’s real genius lay not only in choosing a new direction but in how he pursued it—carefully balancing continuity with reform, and ideology with pragmatism. China’s transformation was ultimately not the result of bold gambles, but of patient, deliberate experimentation.

4/ Is copying the real secret to success?

China’s manufacturing dominance is often dismissed as mere imitation. According to critics, China is a nation copying Western technologies without truly understanding them. But this caricature misses the essence of what has driven China’s economic transformation over the past decades.

What China mastered isn’t simple replication, but imitation-driven competition: a ruthlessly effective system in which imitation becomes the launchpad for genuine innovation. This model has recently played out across industries, from solar panels to smartphones to electric vehicles.

The process typically begins with the central government designating a sector as strategically important—often as part of the CCP’s Five-Year Plan. Provincial governments then race to develop specialised industry clusters, knowing that local economic success can translate into national recognition and career advancement within the Party. Capital floods in, meeting China's deep reservoir of entrepreneurial energy. Hundreds of firms emerge, and reverse engineering of foreign technologies becomes commonplace.

What follows is intense, often chaotic competition. As Arthur Kroeber put it in his book China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, “China builds an entire industry ecosystem and watches to see which pieces survive.” This kind of internal Darwinism is a defining feature of China’s model—and often misunderstood in the West.

American manufacturing entrepreneur Sam D’Amico captured this dynamic on the Odd Lots podcast:

[Electric vehicle maker] BYD is Guangdong province’s champion—so it’s more or less like California having its own. And [battery giant] CATL is Fujian’s champion—kind of like Texas having its own industrial giant.

But unlike US governors, provincial CCP leaders in China aren’t running for re-election—they’re striving to rise through the CCP ranks. Success is judged on economic performance, not votes.

The imitation-driven innovation model was already in motion by the time Jiang Zemin succeeded Deng Xiaoping as paramount leader in the 1990s. What Jiang did was elevate it to the level of official strategy through the “Go Out” policy (走出去战略), which encouraged entrepreneurs and students to study abroad, learn from foreign companies and universities, and bring that knowledge back to China. This marked a new phase, where the state not only tolerated imitation, but actively supported global learning as a way to accelerate domestic innovation.

At the entrepreneurial level, AI pioneer and venture capitalist Kai-Fu Lee describes a similar pattern. In his book AI Superpowers, he writes that Chinese tech startups enter “gladiatorial competition,” where copying is merely the price of admission. Real success depends on adapting, refining, and outpacing peers. In his words, Chinese founders must “evolve or die.”

Finally, there's a cultural dimension to consider. Chinese education places strong emphasis on repetition and the mastery of fundamentals—beginning with the meticulous copying of written characters. The mindset is clear: form is learned before invention.

I recognise this pattern from my own years studying music, particularly jazz. Jazz bassist Marcus Miller, one of my idols, once said he didn’t find his musical voice by trying to be original. He kept playing others’ lines until, one day, he heard a recording and thought, “Oh, that’s me.” Mastery came before originality. This is precisely what Chinese firms seem to understand: thorough imitation creates the foundation for genuine innovation. Just as Marcus played others' lines until his own emerged, Chinese firms copied meticulously until they developed their own distinctive capabilities.

So I’m saying to Lenny White, “Man I really want my own sound, how do you do it?” And he says, “You can’t worry about it, you just keep playing, and keep playing, and then one day, you’re going to hear a recording of yourself and go, ‘Oh that’s me.’” So he gave me some real abstract Karate Kid kind of instructions on how to get your own sound.

French economist Philippe Aghion offers theoretical backing for this model. His groundbreaking research on “neck-and-neck firms” shows that competition between technological peers spurs innovation—exactly what happens in China’s industrial clusters.

And this isn’t uniquely Chinese. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the US—then a developing economy much like China today—built its early industrial base by borrowing liberally from Britain, especially in textiles. American entrepreneurs copied British machinery, improved it, and eventually leapfrogged their former mentors.

It’s ironic that the very complaints Western countries now make about Chinese copying were once heard across the Atlantic in reverse. What China has done is not aberrant—it’s a well-trodden path of industrial catch-up, executed at an unprecedented speed and scale. In this context, copying isn’t the endgame. It’s the first step on the road to innovation leadership.

5/ Beyond cheap labour: what's China's true advantage?

For years, Western narratives about China’s manufacturing power have leaned on a comforting myth: that its success stemmed solely from cheap labour. If that were true, then rising wages would eventually erode China’s edge—and manufacturing might return to the West. But that story was never accurate, and today it’s dangerously misleading.

When China joined the WTO n in 2001, many in the West claimed to be preparing for the so-called “China shock.” In reality, few took meaningful action. In my native France, I distinctly recall textile manufacturers in the north repeating the mantra of readiness without changing anything—like characters in an Italian opera endlessly singing andiamo while never leaving the stage. In truth, many of these firms likely assumed that the state would shield them when the moment came—that some form of backstop or bailout would arrive to cushion the blow. When tariffs finally dropped, however, these companies were wiped out almost overnight. Their collapse only reinforced the myth that China’s edge was simply cheaper workers.

In truth, China began with low-cost labour in the 1980s, but then steadily climbed the ladder of increasing returns that define industrial excellence. As analyst Dan Wang notes, the true output of a manufacturing sector isn’t just physical goods—it’s the know-how embedded in people. This process knowledge—the hard-won, intuitive understanding of how to make production smoother, faster, and more reliable—can’t be captured in manuals. It builds over time, through practice, as in this video:

This process knowledge is particularly crucial in advanced manufacturing, where success depends not just on assembling parts but on integrating sophisticated technologies. In EV production, for example, the challenge isn't simply putting a car together—it's mastering the complex interplay of battery chemistry, thermal management, software systems, and precision engineering. China's leap from traditional manufacturing to advanced manufacturing happened because it systematically built this layered expertise.

Formula 1, which similarly combines high-performance hardware and software, offers a helpful analogy. Regulations are tight, designs are exposed, and innovation is quickly copied. Yet it’s not the blueprint that wins championships—it’s the engineers who instinctively know how to fine-tune. As explained at length in Brawn: The Impossible Formula 1 Story on Disney+ (presented by Keanu Reeves, no less), when Brawn GP debuted its double diffuser design in 2009, it dominated the early season. But by mid-year, rivals had reverse-engineered the breakthrough—and the team barely held on to win the title. In F1, as in manufacturing, what matters is not just the idea but the ability to execute it with precision, repeatedly. That’s why teams enforce “gardening leave” when top staff exit: process knowledge walks out the door with them.

This also explains why Apple CEO Tim Cook has said Apple’s production isn’t in China because labour is cheap—it hasn’t been for years—but because of the depth of skilled talent. Cook once remarked that all the production engineers in the US could fit in a ballroom; in China, you’d need several football fields.

This depth and concentration of production talent is particularly crucial for advanced manufacturing, where success depends on the complex orchestration of hardware and software integration. When Apple manufactures its devices, the challenge isn't simply assembling components—it's coordinating precision engineering, materials science, and sophisticated testing systems at massive scale. China's ecosystem doesn't just offer hands; it offers minds trained in the advanced manufacturing disciplines that modern production requires.

The scale is staggering. Take BYD, the Chinese electric vehicle giant. When a friend of mine—a Paris-based journalist covering the auto industry—questioned the company’s claim of a 5-minute battery charger (now potentially overtaken by CATL, another Chinese company!), a senior executive responded matter-of-factly: “Of course. We have 120,000 engineers; they have to deliver breakthroughs now and then.” With a total BYD workforce nearing a million, that number is plausible—and telling. At that scale, innovation becomes routine.

This depth of capability also explains China’s dominance in high-volume, cost-sensitive markets. Consider Impulse Labs, the US stove manufacturer headed by Sam D’Amico, whom I already quoted above. According to Sam, when they tried to reshore production of a simple stamped sheet metal part, they found the US cost was $700—compared to under $200 in China. As he explained on the Odd Lots podcast, the gap wasn’t about wages. It was about industrial orientation. US manufacturing has become focused on small-batch, high-spec sectors like defence and medical devices—not consumer hardware at scale.

And that matters. Quality and consistency are non-negotiable in consumer markets, where faulty hardware means returns, reputational damage, and business failure. Achieving low cost and high quality at massive scale demands years of iteration, thousands of small optimisations, and a workforce with deep, intuitive knowledge. That’s why virtually every hardware startup looking to scale ends up partnering with Chinese manufacturers, the only ones able to deliver. In the tech world, we’ve seen this pattern again and again—in the US as well as in Europe.

The one area where China has yet to achieve dominance is advanced semiconductor fabrication. Taiwan's TSMC still leads in cutting-edge chip production, creating both a strategic vulnerability for China and a flashpoint for geopolitical tension. Beijing's push to build domestic chip capabilities—intensified after US sanctions—may be the ultimate test of its manufacturing model. Success here would complete its technological sovereignty; failure would leave a critical dependency.

All in all, China’s true manufacturing advantage isn’t cheap labour. It’s the compound effect of decades of accumulated expertise, built through relentless repetition and deep specialisation. Western policymakers now hoping to “reshore” industry face a difficult truth: the knowledge of how to manufacture—efficiently, reliably, at scale—has withered. Rebuilding it will require more than reopening factories. It demands time, talent, and the patient cultivation of an industrial culture that many Western nations let fade while they theorised about post-industrial futures—and, in the case of the US and UK, chased the sky-high (and short-term) returns of financialisation.

6/ Does manufacturing explain Xi’s Chinese tech crackdown?

By the mid-2010s, China had become home to some of the world’s most valuable tech companies. Names like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu and Didi had grown from local startups into global giants. To understand this rapid ascent, it’s important to recognise that tech adoption in developing economies often follows a different path than in the West.

Unlike advanced economies weighed down by legacy systems for payments, commerce or communication, China could build its digital infrastructure from scratch. This enabled “leapfrogging”—skipping over intermediate technologies to adopt the most advanced solutions directly. Chinese firms didn’t need to retrofit outdated models; they could build entirely new systems optimised for the digital age.

This was especially evident in e-commerce, logistics, digital payments, social media and mobility. The result was a new kind of digital ecosystem, typified by “super apps” like WeChat and Alipay. While Western tech companies tend to specialise in doing one thing well, Chinese platforms bundle dozens of services—messaging, payments, bookings, gaming, government access—into a single seamless experience.

This ecosystem approach was reinforced by the absence of major Western rivals. As Kai-Fu Lee noted (still in AI Superpowers), Google (where he worked at the time) effectively exited China in 2010. Facebook and Twitter were blocked by the infamous “Great Firewall,” while Uber bowed out in 2016 after being outmanoeuvred by Didi, which absorbed its China operations that August.

The combination of state-imposed barriers and fierce domestic competition created a pressure cooker of innovation. Chinese tech companies battled each other relentlessly while being shielded from global challengers. The result was a generation of firms that could hold their own against Silicon Valley—and in some cases, outpace it. ByteDance, with TikTok, even cracked the holy grail: building a Chinese product that succeeded globally on its own terms.

By 2018, “Peak China tech” had arrived. Western observers, myself included, marvelled at the speed and scale of innovation. Mike Moritz of Sequoia wrote a much-circulated piece (in the Financial Times) urging Silicon Valley to learn from China. Kai-Fu Lee predicted Chinese dominance in AI. The mood was shifting: perhaps China—not the US—would define the next technological era.

But from Beijing’s perspective, this wave of consumer tech success posed three problems.

First, as software was “eating the world,” the economy risked drifting too far toward domestic consumption and away from the export-driven manufacturing that had powered China's rise until then. Simply said, a nation of app developers and online shoppers didn’t align with the Party’s vision of industrial strength.

Second, capital and talent were flowing into platforms rather than into semiconductors, advanced manufacturing or hard tech. As analyst Emily de La Bruyère has argued, China’s industrial policy is not just about invention—it’s about application and scale. It’s not that you hold the patent; it’s that you’ve built the hardware, networks and supply chains to make it matter. Consumer tech threatened to divert focus from those strategic foundations.

Third—and perhaps most sensitive—China’s tech CEOs had become global celebrities. Jack Ma wasn’t just a tycoon; he had a platform, international influence and opinions on regulation. But in the Party’s view, tech moguls aren’t independent agents—they’re custodians of national goals. As one analyst put it, “Jack Ma may be an entrepreneur, but he’s also a CCP corporate trustee. And his usefulness had reached its shelf life.”

The crackdown began in November 2020, when regulators abruptly halted Ant Group’s record-setting IPO—just days after Ma criticised China’s financial system. What followed was a sweeping campaign targeting education tech, gaming, ride-hailing and more. By mid-2021, over $1 trillion had been wiped from Chinese tech valuations.

This wasn't merely punishment for Ma's hubris. The state was sending a clear message: no individual or company, however successful, could stand outside Party control. More importantly, it was reallocating capital from consumer platforms to ‘deep tech’—semiconductors, advanced materials, industrial automation—sectors deemed crucial for long-term competitiveness.

All in all, this wasn’t simply punishment. It was a strategic reset. The CCP was reallocating resources toward sectors it considered critical for long-term competitiveness: semiconductors, electric vehicles, clean energy, robotics and advanced manufacturing. In the age of computing and networks, the logic of industrial development runs downstream to upstream: first, let consumer-facing firms experiment with value propositions; then redirect capital and policy to secure the foundational layers.

The timing proved shrewd. As software and hardware increasingly converge—with firms like Xiaomi building cars and manufacturers like BYD embedding advanced software—China’s pivot looks prescient. AI too is evolving: it no longer depends solely on algorithms, but on integrated systems, chips and infrastructure.

In hindsight, the tech crackdown looks less like authoritarian overreach and more like calculated repositioning. By reining in consumer tech and reorienting toward industrial depth, China was preparing for the next phase of global competition—one in which the fusion of bits and atoms will determine who leads.

7/ Is manufacturing eating the world now?

For years, like many in tech, I saw Marc Andreessen’s 2011 essay Why Software Is Eating the World as the definitive thesis of our era. It was hard to argue with: software platforms were disrupting everything from media to transport, and Silicon Valley seemed unassailable as the global centre of innovation.

But we may now be entering a new phase—one where China is already out in front. David Galbraith recently articulated this shift in a short but foundational thread: the era of computing and networks has evolved through three distinct stages. First came digital-only (social media, SaaS); then digital meets physical (Uber, Airbnb); and now, digital embedded in physical systems—from EVs to drones to humanoid robots. It’s in this third era, where software is baked into hardware, that China shines.

As ever with China, the numbers are bracing. It produces over 60% of the world’s EVs, leads global battery and solar panel production, and—despite Western efforts to slow it—continues advancing in semiconductor fabrication. While the US still leads in pure software and chip design, China has spent the past decade methodically building supply chains and manufacturing capabilities that make hardware a strategic asset.

This didn’t happen by accident. Long before most Western leaders, China’s policymakers understood that the fusion of software and hardware would shape the next frontier of technological power. While Silicon Valley was fine-tuning platforms and enterprise tools, Beijing was laying the groundwork to lead in AI-powered physical systems.

This is the essence of advanced manufacturing: not just making things, but creating intelligent, interconnected systems. Unlike traditional manufacturing which competed on labour costs and production volumes, advanced manufacturing competes on the ability to integrate software, AI, and robotics into physical products at scale.

Consider BYD. Unlike Tesla, which builds cars in China but doesn’t control its full supply chain, BYD is vertically integrated—from battery production to software. It now outsells Tesla globally and has started giving away its self-driving software stack. That’s not a bug; it’s the strategy. Undercut Western carmakers (like Stellantis) who plan to monetise software à la Silicon Valley, and boost hardware adoption instead.

This tactic—commoditising software to drive hardware sales—echoes Microsoft’s strategy against Netscape in the 1990s, but it also reflects a deeper logic: what the late Clay Christensen called the “law of conservation of attractive profits”. As modular, open software erodes margins in one part of the value chain, profit opportunities reappear at an adjacent layer—often where integration, scale and proprietary control still matter. In China’s case, that layer is increasingly physical: batteries, robots, chips, EVs. When DeepSeek releases a powerful open-source AI model, it's not just competing on price—it's shifting value from bits to atoms, from the software layer to the integrated systems it powers. This strategy mirrors what Chinese hardware firms are doing across industries: commoditising the software layer to drive adoption of their physical products.

And that matters. Today’s hardware isn’t just machinery—it’s software-enabled systems. EVs are rolling computers. Drones are flying sensor networks. Humanoid robots are AI in physical form. As I argued recently in a piece on defence innovation, this fusion of digital intelligence with physical capability is where the game is now being played.

Which is why China’s pivot from consumer tech to advanced manufacturing—originally seen as a crackdown—now looks more like a strategic reallocation. The engineering talent that once built super-apps is being redeployed to what Emily de La Bruyère calls “applications at scale”: full-spectrum technological systems that combine smart software with production might.

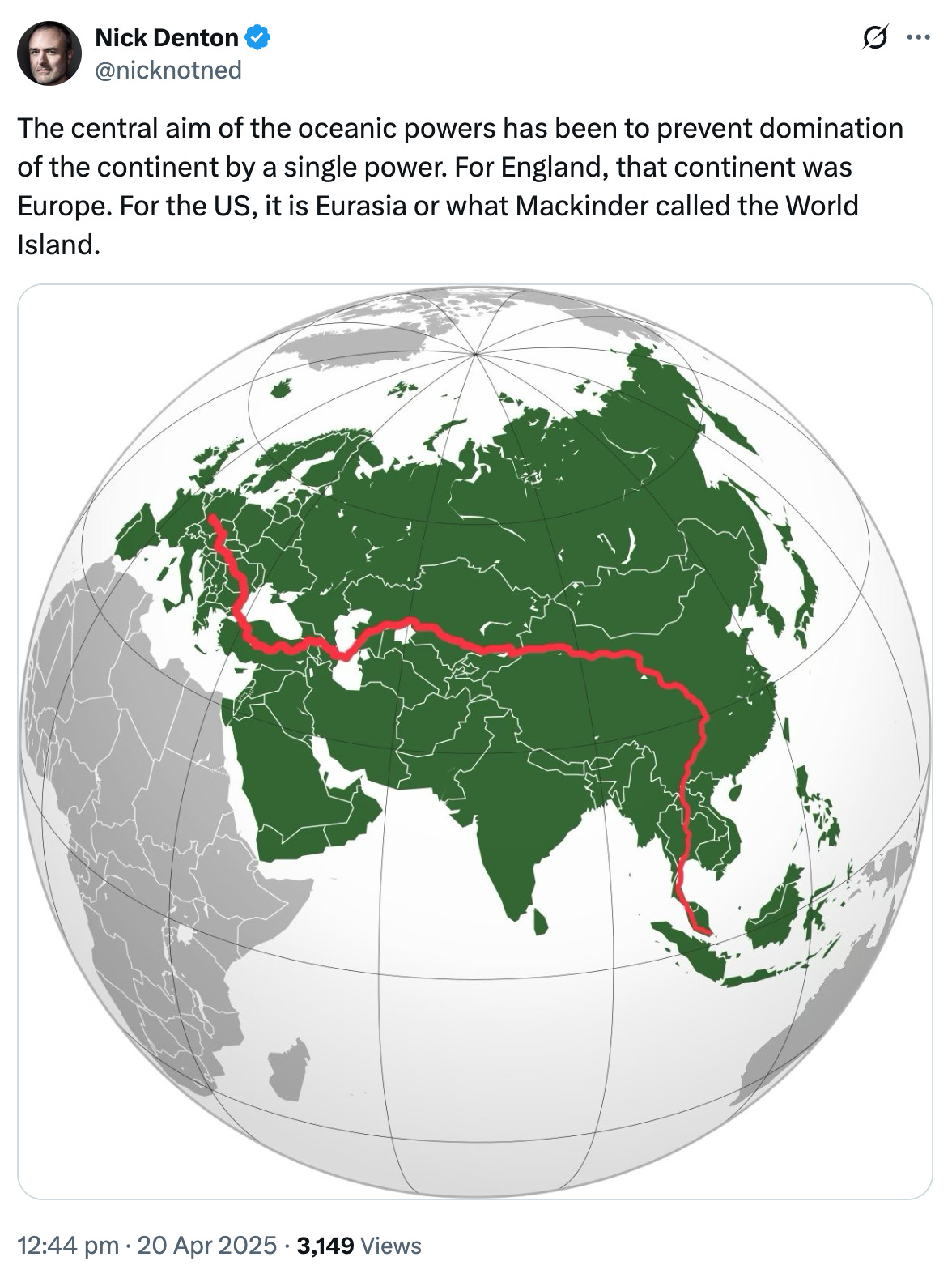

This creates a real challenge for the West. Even America’s most iconic hardware firms—Apple, Tesla—still depend heavily on Chinese manufacturing. Apple may design in Cupertino, but it assembles in Shenzhen. And as Nick Denton notes in a thread echoing David’s, if you combine China’s domestic market with Southeast Asia and parts of Europe, you’re looking at an economic zone ten times the size of the US. At that scale, network effects become a geopolitical force.

It's worth noting that India, often touted as China's rival, has failed to replicate this success despite similar population scale. India's fragmented governance, limited state capacity, and lack of focused industrial policy have prevented it from building the integrated supply chains and process knowledge that define China's advantage. While India hosts impressive software talent, it remains largely peripheral to global hardware supply chains.

The most telling sign of what’s coming may be the rise of humanoid robots—machines that don’t just assemble other products, but will soon manufacture other machines. This is what some have begun to call a “manufacturing singularity”: the point at which general-purpose, intelligent machines can build and improve other intelligent machines. It’s happening faster than many expected.

China's edge here isn’t just scale or speed. It's systemic application. As it has throughout its rise, China’s real strength lies in turning technology into policy, and policy into coordinated national capability. What began as imitation has evolved into innovation—at industrial scale.

The West still leads in pure software and chip design. But as products become more intelligent and connected, the real value lies in integration—in fusing code and components, algorithms and supply chains. At that intersection, where bits meet atoms, China’s long-term investment in infrastructure, talent, and industrial coordination is starting to pay off.

As stated by David, it may turn out that the future isn’t about software eating the world, but about smart manufacturing—software embedded in machines—eating software itself. And by that measure, China may already be standing on the commanding heights.

8/ Is the West becoming the new developing economy?

History offers an uncomfortable parallel. In the 19th century, the US rose to prominence in steel and heavy engineering by first adopting European methods, then surpassed them in the 20th century through its dominance in automobiles and mass production. Fast forward to the 21st century: China has not only caught up with the industrial model that defined the last century (the age of the automobile and mass production) but is now moving ahead in the age of computing and networks—just as the West begins to realise that the real edge lies in embedding those very technologies into physical hardware, which demands excellence in… advanced manufacturing.

This role reversal has left the West in the unfamiliar position of playing catch-up. Meanwhile, many in the West still misunderstand what manufacturing has become. Political rhetoric often conjures a nostalgic image: assembly lines filled with blue-collar workers earning stable, middle-class wages. But today’s manufacturing is a different beast—capital-intensive, highly automated, and capable of producing strategic value without generating mass employment. While it may create some skilled jobs, modern manufacturing can’t revive the broad-based social contract of the post-war era. The fixation on reshoring may instead signal a deeper crisis: the West’s failure to imagine new paths to shared prosperity in an age where the most productive sectors employ few. Until that’s addressed, the promise of “good jobs” through manufacturing will remain just that—a promise.

Indeed, the reality is stark: today’s factories employ more robots than humans. Automation and AI now run production lines, with only a handful of highly skilled engineers on site. As Joe Studwell noted in How Asia Works, manufacturing once drove productivity while creating mass employment. But that equation no longer holds. Traditional manufacturing paired mass production with large workforces; advanced manufacturing delivers complex output with minimal human input. It’s now a knowledge industry, powered by software, robotics, and integrated systems.

So-called “lights-out” factories—highly automated, low-headcount operations—are becoming the norm. Tesla’s gigafactories employ a fraction of the workforce seen in 1970s car plants; TSMC’s most advanced fabs are near-fully automated. Even in China, manufacturing employment has peaked despite rising output. The few roles that remain require specialised technical skills—robotics, AI systems, quality engineering—not the kind of work that can absorb mass unemployment or revive struggling regions.

Despite this reality, many Western leaders continue to hold out hope for a return to the broad-based prosperity once fuelled by manufacturing. Rather than dismiss that ambition, it may be more useful to rethink the path toward it. Joe Studwell’s playbook for economic development—though originally crafted for agrarian economies transitioning to industrialisation—still offers valuable insights. Its core principles remain relevant today:

First, active management of the workforce is crucial. Just as the CCP under Deng Xiaoping kept rural Chinese productive while creating urban manufacturing jobs, the West must maintain employment in traditional sectors while rapidly building advanced manufacturing capacity. This means keeping workers engaged in productive roles while simultaneously training them for the high-tech factories of tomorrow.

Second, export discipline is a must. Western firms must prove they can compete head-to-head with Chinese manufacturers at a global scale. This isn’t about shielding domestic markets with tariffs; it’s about pushing local companies to compete at global standards of quality, efficiency, and innovation. Fewer safe harbours, more tough competition.

Third, we would need financial repression: channelling domestic savings into strategic industrial investments rather than speculative ventures like property or financial engineering. And this is problematic, as it runs counter to everything the West has championed since the 1980s. When the Trump administration floated policies aimed at suppressing domestic consumption and boosting manufacturing investment, they were largely dismissed. And while there is renewed talk of a return to financial repression (see Russell Napier and Izabelle Kaminska), it’s highly doubtful that such an approach—however necessary it may be for the West to regain its competitive edge—is politically sustainable.

Indeed, for the West to emulate the Deng–Jiang playbook in today’s era would demand extraordinary patience and sacrifice. China's own rise in traditional manufacturing took decades of deferred gratification, with the population accepting lower living standards to fund industrial development. It meant sending generations of students abroad to acquire foreign technologies, despite the risks of brain drain. It meant creating special economic zones to absorb and adapt foreign expertise.

Emulating this approach presents insurmountable obstacles for the West:

First, China remains largely impenetrable to Western understanding. The language barriers, cultural differences, and growing political tensions make it nearly impossible for Western students and professionals to gain the insights that China's ‘sea turtles’—Chinese students who studied abroad and returned home—brought back over the past decades.

Second, Westerners have grown comfortable in their post-industrial bubbles. Unlike the hungry Chinese entrepreneurs of the 1990s, few Western professionals are willing to endure the hardships necessary to truly understand and adapt Chinese industrial methods. The idea of spending years in an unfamiliar, often hostile environment seems increasingly alien to Western sensibilities.

Third—and perhaps most critically—we’ve convinced ourselves, for better or worse, that China is the new adversary. Instead of fostering engagement and learning as in Jiang's “Go Out” policy, many parts of the West, starting with the US, are pursuing a “Close Down” strategy based on the belief that China is simply a reincarnation of the Soviet Union. (Meanwhile, some, like Niall Ferguson below, even argue that it's the West that now resembles the stagnating late-Soviet system—complacent, inefficient, and ideologically rigid.)

About that idea of a second Cold War: Recent research by Henry Farrell and colleagues provides empirical evidence that Western actions accelerated China’s technological decoupling. Their analysis of Chinese government documents reveals a sharp rise in references to ‘technological security’ following the 2013 Snowden revelations, which exposed the extent of American surveillance capabilities. This was followed by a surge in rhetoric around ‘technological independence’ after US sanctions against ZTE and Huawei in 2018–2019.

Rather than being solely the product of a long-term Chinese strategy, this decoupling—and China’s subsequent push to race ahead—may in fact be a direct response to successive waves of American provocation. It echoes the early Cold War dynamic, where tensions with the Soviet Union were driven not only by geopolitical rivalry, but also by the pressures of US domestic politics and a rising Red Scare, which pushed the Truman administration and others to draw a hard line.

All in all, like in Greek tragedy, by trying to prevent the outcome of Chinese technological dominance, Western powers may have unwittingly accelerated it.

An alternative approach for the West would be inviting Chinese manufacturers to expand operations in our markets, forming joint ventures to enable technology transfer and skills development. This would require offering what China offered Western firms in the 1990s: deep markets, fast-growing purchasing power, and a welcoming business environment.

We would also need our own version of Dragonomics—the pioneering research firm founded by Arthur Kroeber and Joe Studwell in the late 1990s to help Western businesses understand China's markets and policies, now part of the asset manager Gavekal. But this time, we'd need analysts explaining Western markets to Chinese investors. The irony is that, thanks to their “Go Out” policy, the Chinese understand us better than we understand them.

The harsh reality is that the West lacks both the political will and social consensus for such radical transformation. We're trapped between recognising China's manufacturing superiority and our inability to make the sacrifices required to catch up. The result is growing reliance on protectionist measures that may slow China's advance but do little to restore Western competitiveness.

9/ Is America abandoning both ends of the market at once?

This all leaves the West with a stark choice. One path is to attempt to revive manufacturing employment through tariffs and industrial policy—even as automation steadily erodes the number of jobs such a revival could plausibly create, and as the economic returns from labour-intensive production continue to diminish.

The alternative is to accept what might be called the “new Britain” model—a direction the UK began pursuing in the 1980s. Faced with deindustrialisation and intensifying global competition, Britain effectively deprioritised manufacturing and pivoted towards high-margin, post-industrial sectors. The economy reoriented around finance, legal and consulting services, media, entertainment, and the upper layers of global value chains—owning, branding, and financing rather than producing. Employment, meanwhile, became increasingly concentrated in proximity services: public sector roles in healthcare and education (typically secure but modestly paid), alongside private sector jobs in retail, hospitality, and care work (often precarious, low-wage, and offering little long-term prospects).

This model echoes a pattern described by the late Clayton Christensen in his landmark book The Innovator's Dilemma: incumbents rationally abandon low-margin segments in favour of high-margin niches. But in doing so, they leave themselves vulnerable. New entrants—like China—initially compete on cost at the low end, then move steadily upmarket, eventually challenging and overtaking the incumbents' core business.

What's especially striking today is that, contrary to Britain, China hasn't moved upmarket by renouncing manufacturing in favour of high-value services; rather, manufacturing itself has moved upmarket. From China’s perspective, traditional, low-value manufacturing has evolved into advanced manufacturing—a domain defined by capital intensity, precision engineering, and deep integration with software, AI, and robotics. As a result, China has successfully moved upmarket without undergoing deindustrialisation. It has retained its manufacturing base while upgrading its technological capabilities and complexity. In many areas, China's advanced manufacturing capacities, which clearly surpass those of the West, are delivering returns that match or exceed those from high-end service sectors. And it's all thanks in large part to its intact and strategically cultivated industrial ecosystem, whereby no process knowledge has been lost along the way.

The irony, in the case of the US, is that it has since moved even further than Britain in embracing a service-dominated model. It is now the global leader not only in financial services (Wall Street) and entertainment (Hollywood), but also in technology—particularly software (Silicon Valley). As a result, the American economy is even more heavily tilted toward high-end sectors built on bits rather than atoms: finance, tech, and intellectual property. Meanwhile, domestic employment growth has been concentrated in proximity services—roles in healthcare, retail, hospitality, and care work that are often poorly paid, precarious, and offer little in the way of advancement or security. It’s a structural shift that helps explain a large part of the contemporary American malaise: an economy brimming with wealth at the top, but offering increasingly grim prospects for those further down the ladder.

In this regard, current US policy reflects a confused and contradictory strategic posture.

On one hand, the Trump administration’s recent efforts to reshore manufacturing—primarily through tariffs—have been uneven and largely shaped by political considerations, with limited evidence so far, according to most economists, that they will ever deliver substantial employment gains. US policymakers should recognise, not least by looking at China, that modern manufacturing is capital-intensive and highly automated; it no longer generates the kind of large-scale employment that once defined industrial economies. Nor is there much appetite among American workers to return to low-margin sectors like textiles or footwear, which have long since shifted to countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia. As Gary Cohn, a former Goldman Sachs executive and Trump’s economic advisor during his first term, pointed out at the time:

I can sit in a nice office with air conditioning and a desk, or I can stand on my feet eight hours a day. Which one would you rather do for the same pay?

At the same time, recent US monetary and fiscal policies appear to be undermining the country's role as the world's financial hub—what I called America Capital Partners in a recent edition—by weakening the dollar and reducing the incentives for foreign capital to flow into US markets. And so, in effect, the US is performing an inverted version of Christensen's framework: it is relinquishing its dominance in high-end services and financial infrastructure, without securing any credible alternative source of high-return economic activity (because you can't build a domestic advanced manufacturing sector overnight). It is a strategy that manages to walk away from both ends of the market at once—abandoning the commanding heights while chasing a manufacturing revival that no longer delivers employment.

Worse still, Trump-era policies have actively undermined the foundations of America's high-end economy on multiple fronts. Moves to weaken the dollar—aimed at boosting exports—also erode the country's attractiveness as a destination for foreign capital, thereby chipping away at the financial sector's global dominance. At the same time, the increasingly adversarial posture toward traditional allies risks closing off key international markets for American tech companies. But the tech sector thrives on scale and interconnectedness; it relies on unified global markets to justify its business models, innovation cycles, and returns. Fragmenting that market doesn't just hurt competitors—it damages America's own strategic assets.

In short, the US is undermining its financial dominance, fracturing and crippling its tech ecosystem, and chasing a manufacturing revival that won't bring back meaningful employment.

Of course, I'm not saying (and neither did Christensen when he was still alive) that it's impossible for an incumbent to innovate and reposition itself favourably. What's certain is that there's an approach that never works: you don't destroy your profitable core business (which in the US case is formed in large part of financial services and Silicon Valley) so that you can build a new business at the margin. Rather, what you do is to create something new and clunky at the margin, far away from the centre.

But is there room for that in the US? If the East Coast is dominated by financial services, California is tech territory, and the Rust Belt is traditional manufacturing, maybe the advanced manufacturing boom will happen somewhere between Texas, North Carolina, and Arizona? Again, let them work hard at delivering just that, but don't destroy the rest.

10/ Where do we fit in the Chinese Century?

As China races ahead in advanced manufacturing and hardware–software integration, the question looms: will the 21st century belong to China? Noah Smith argues it probably will—though not in the same way the 20th century belonged to America. In a recent edition of his newsletter Noahpinion, "Will this be the Chinese Century?", Noah makes a compelling case that China's rise represents a fundamental shift in global power dynamics.

Building on Noah's analysis, I want to explore how China's model diverges sharply from the mass-production paradigm that defined America's rise. The US built its dominance on standardised goods made by millions of workers in a consumption-led economy. China, by contrast, leads in automated, high-end manufacturing powered by a smaller, more skilled workforce. It is less about scale than integration—blending robotics, precision engineering, and AI with formidable state coordination.

Noah points out that “the American century” was exceptional in its breadth: economic might, military supremacy, cultural influence, technological leadership, and the provision of global public goods. China's ascent, though equally transformative, follows a different blueprint. As Noah notes, its state capacity now exceeds America's historical peak—evident in what he calls China's “marvel of size, resource mobilization, and innovation,” visible in projects like its vast high-speed rail network. According to Noah's analysis of UN predictions, by 2030, China could account for nearly half of global manufacturing output, “a share higher than the US ever achieved except for a brief moment after World War 2.”

Yet Beijing shows little interest in replicating the American model of liberal affluence. Per capita wealth may remain below Western levels, and I would argue this is by design. The Communist Party actively suppresses the rise of a consumption-driven middle class. High household savings are channelled into infrastructure, strategic sectors, and technological self-reliance, still in line with Joe Studwell's financial repression playbook. Rising living costs, a limited welfare state, and the hukou system further dampen consumer spending—and likely contribute to China's sharp demographic decline, the one threat that could ultimately prove its undoing.

This is not a policy failure—it's the logic behind China's “dual circulation” strategy. Officially launched in 2020, dual circulation aims to balance domestic demand (the “internal circulation”) with global trade and investment (the “external circulation”). But in practice, although China is less reliant on exports in relative terms than Germany or South Korea, for instance, the national strategy is still heavily tilted toward the external: exports, production, and state-led investment remain the backbone. Consumption is encouraged rhetorically but still constrained structurally and politically.

Currency policy reflects this balancing act. In the early 2000s, China kept the renminbi undervalued to support exports. Since 2005, it has allowed gradual appreciation, aiming to contain inflation, reduce input costs, and build credibility for the renminbi globally. Yet capital controls remain firmly in place. Full liberalisation would bring transparency and market risk—two things the Party is not prepared to accept.

Technological leadership, too, follows a distinct pattern. Noah observes that China is “a highly innovative country, but... its innovations tend to be a blizzard of incremental improvements with few dramatic breakthroughs.” I would expand on this to suggest China is less focused on breakthrough innovation than on scaling and controlling new technologies. It excels at industrialising mature ideas, especially where global IP protections are weak. From the Party's perspective, radical innovation is destabilising; safer to adapt and refine than to disrupt.

On the cultural front, Noah predicts that “China's leaders will also probably remain paranoid about allowing in foreign ideas” and that “artistic and cultural ferment will arrive in China only weakly, and with a lag.” While American influence flowed through Hollywood, universities, and open debate, China's soft power is constrained by censorship and surveillance. The ‘Great Firewall’ doesn't just block information—it inhibits cultural expression. Chinese media and art rarely gain global traction.

Above all, Noah highlights that China appears uninterested in supplying global public goods. Where the US Navy once guaranteed freedom of navigation (about that, check Peter Zeihan 👇), China's naval power is narrowly self-interested. As Noah puts it, “I expect China to be a far more selfish power than America was in the late 20th century.” Where American research often served humanity at large, Chinese science serves national goals. The result is a more transactional, less universalist superpower—closer in spirit to early 20th-century America than to the post-war Pax Americana.

At the same time, the US appears to be turning inward—marked by protectionist trade policies, political polarisation, and growing scepticism toward global alliances. In the space this creates, neither the US nor China seems positioned to lead the global financial system outright. Instead, a multipolar future is taking shape: China consolidating its dominance in industrial tech and manufacturing; the US striving to restore financial and technological supremacy through reshoring and strategic investment; and Europe, despite its internal frictions, emerging as a regulatory, diplomatic, and sustainability-oriented middle power.

And so, if this is to be the Chinese Century, it will be more economically powerful but less culturally resonant, more technologically advanced but less inclusive, more competent in execution but less generous in vision. As Noah writes:

A Chinese Century will, in many ways, be a downgrade from the American Century. Perhaps the US efflorescence was a very rare and special thing, whose like we will not soon see again.

Looking ahead, I see three broad scenarios as plausible:

Manufacturing Singularity. China achieves dominance in self-replicating manufacturing systems—machines building machines—creating a structural lead in production efficiency and industrial coordination. With unmatched scale, data integration, and state-backed investment, it reaches levels of productivity that are difficult for decentralised economies to match. The West, particularly the US and Europe, finds a new niche: focusing on high-value design, research, and financial and legal services. In this version of the future, the US and EU begin to resemble Britain after it ceded industrial leadership to America in the late 19th century—no longer the engine of global manufacturing, but still rich, culturally influential, and deeply embedded in the international system. This is not collapse, but it is a repositioning—and one that, with foresight, can be stable and prosperous.

Fragmented Spheres. The global economy fractures into three main blocs: a China-centric manufacturing system, a US-led alliance with regional production hubs, and a more regulatory-driven, sustainability-focused EU sphere. Each bloc develops its own technological standards, data governance models, and supply chain networks, reducing global efficiency but enhancing geopolitical resilience. However, fragmentation does not mean equality. China's bloc, thanks to its industrial scale, infrastructural dominance, and integration with the Global South, outpaces the others in speed, cost, and technological adaptation. The US and EU remain significant, but increasingly play catch-up—innovating at the frontier but struggling to industrialise at scale. They remain important, but in many sectors, they are also-rans.

Technological Surprise. A breakthrough in AI, quantum computing, biotech, or materials science upends current trajectories and inaugurates a new techno-economic paradigm. Carlota Perez’s theory of great surges of development reminds us that such revolutions do not arrive in a smooth arc—they come in waves. While the current surge, rooted in computing and networks, is still unfolding, history tells us that another transformation will eventually arrive. It may be 20 or 30 years away, but when it comes, it will reshuffle global leadership. Whether China’s scale gives it the edge, or whether more open, experimental ecosystems in the West prove better suited to the early stages of the next surge, remains uncertain. What is clear is that we are still midstream in the current paradigm—and for now, China is mastering it.

In the meantime, the image that best captures the current shift is that lights-out factory in Shenzhen at the top of this (long, sorry) essay: machines working in silence, guided by sensors and algorithms, while a handful of engineers observe from a distance. This is not the Fordist factory of the American century—no bustling shop floor, no middle-class workers with union wages. It is the future of manufacturing: brilliant, efficient, largely jobless, and increasingly Chinese.

The real question is no longer whether the West can bring back the factories of yesterday. It is whether it can find its place in the industrial world of tomorrow.

I’ve been writing and interviewing about China since at least 2017. Here’s everything I’ve managed to dig up from the archive:

An examination of China's network-focused industrial policy and its challenge to Western approaches: China's Industry Policy w/ Emily de La Bruyère (May 2021).

A dialogue on Chinese tech entrepreneurship and its unique institutional context through conversation with writer and analyst Lillian Li: Chinese Tech w/ Lillian Li (April 2021).

A comprehensive overview of the US-China technological rivalry and its implications for Europe through a collection of essays: All About the US-China Rivalry (December 2020).

A critical analysis of Jack Ma's shifting fortunes within China's political economy following Ant Financial's halted IPO: Jack Ma's Future (November 2020).

An analysis of China's approach to industrial policy, focusing on applications and networks rather than basic research: Industrial Policy: China Gets It, We Don't (October 2020).

An examination of China's face-saving approach to the TikTok ban and its cultural significance in US-China relations: China Saving Face on TikTok (September 2020).

A primer on the CCP's structure, evolution, and pervasive role in Chinese society and tech sector: A Primer on the Chinese Communist Party (September 2020).

A personal reflection on my evolving relationship with China, from childhood impressions to informed analysis as a tech observer: My Personal Journey with China (August 2020).

A discussion of the growing strategic and economic rifts between China and the Western world in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: China Drifting Away? (May 2020).

A comprehensive exploration of China's development model, technological advancement, and geopolitical position in the Entrepreneurial Age: The Rise of a New China (April 2020).

A curated bibliography of twelve influential books examining China's history, politics, and economic development for English readers: 12 Books on China (May 2019).

An analysis of China's emerging economic safety net and its relationship to political legitimacy within its modernising but non-Western paradigm: China: A Greater Safety Net in the Making (April 2018).

An analysis of China's digital expansion strategy via economic influence and the Belt and Road Initiative, positioning Chinese tech giants for global dominance: When China Rules the Global Digital World (December 2017).

A discussion of China's technological rise and its implications for European startups, highlighting how China has evolved from follower to pioneer in the age of computing and networks: The Family in China (November 2017).

Sign up to Drift Signal if you don’t want to miss the next issues 🤗

From Paris, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas

Really well thought and inisghtful. As a China originated, US educated, and Europe working corporate lawyer, I have to say there are a couple things which I disagree with or think you have left out though:

1. The legacy of the Mao Era, which often referred to as "the former thirty years" after CCP took over China. Such legacy, such as land reform, Soviet dominated economic development and technolgy transfers, military driven constructions in remote areas, etc. etc., all paved way for the waves of industrial revolutions that happened in Deng era;

2. Crack down on IT giants. Many believe that it is necessary because these IT giants are increasingly drawn towards platform based business models, while such platforms often are public infrastructures like railways, which should not be owned privately. Also, the IT giants were getting too comfortable with profits reaped domestically with such platforms while the expectation is for them to to compete globally.

3. The landscape of Chinese century. The Chinese century is probably rushed because of the unanicipated quick down fall of the PAX Americana. So it remains to be seen how the landscape will look like. But I personally do not believe it will be limited to the economic level. In fact, there are already some cultural phenomenons emerging in the past year, like the video game Black WuKong, the movie NeZha, the APP Rednote.

Excellent essay. Thanks Nicolas. Many questions asked about the future