Europe's tech ecosystem is at an inflection point. After years of playing catch-up to Silicon Valley and watching as China forged its own path to tech dominance, European founders, investors, and business leaders are recognising the need for a fundamental strategic reset.

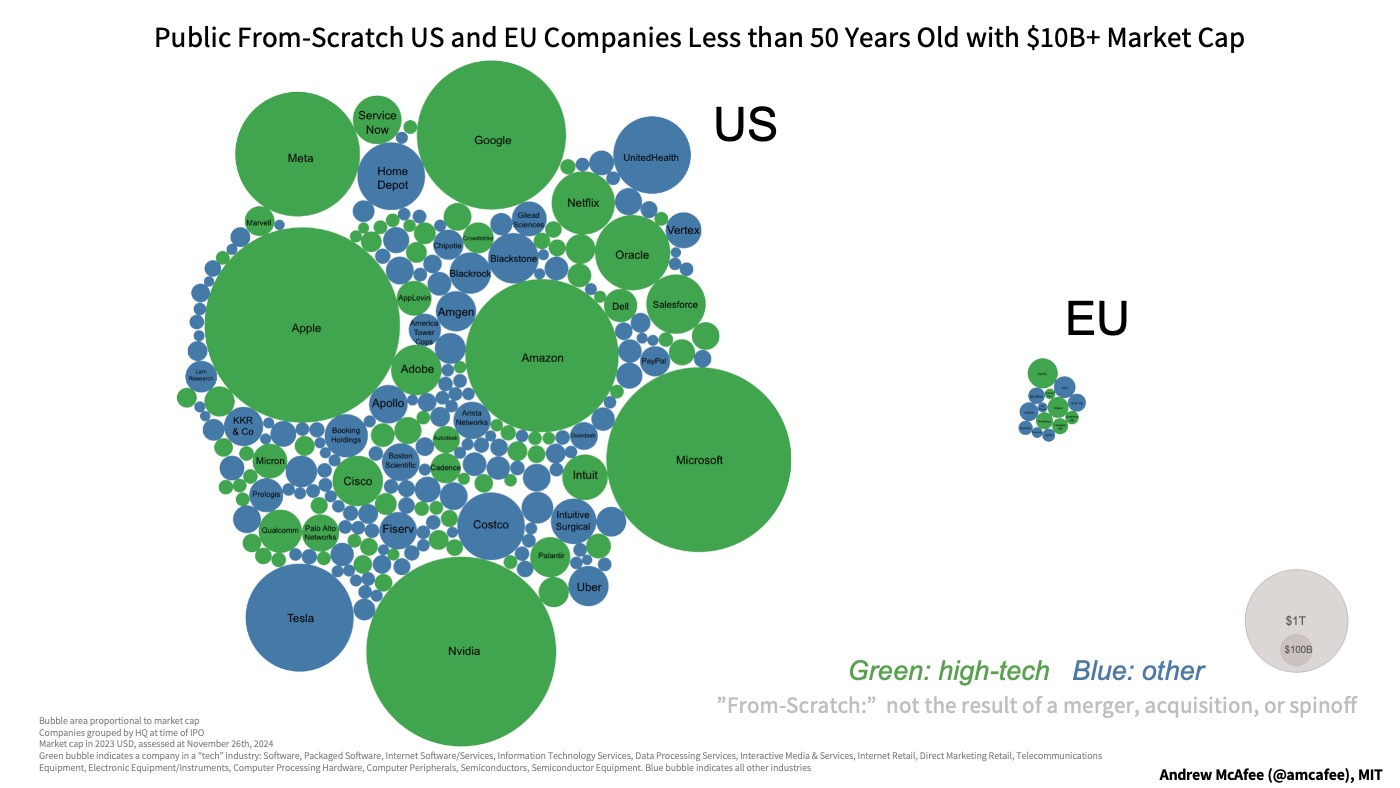

For too long, Europe has tried to emulate Silicon Valley's approach to building tech companies, with limited success. Despite pockets of excellence, the gap remains stark: not a single European tech company ranks in the global top 20 by market cap, and successful exits remain rare exceptions rather than consistent outcomes.

Yet amid these challenges, I see reason for optimism. A new generation of players is emerging who understand that Europe must develop its own distinctive approach—one that transforms our supposed weaknesses into strategic advantages. European tech leaders are beginning to recognise that our fragmented markets, regulatory frameworks, and distributed talent can become assets rather than liabilities in the right strategic context.

The recently launched Project Europe represents just one of many initiatives that have flourished recently. While its focus on early-stage development is understandable, I believe Europe's fundamental challenge lies deeper—in identifying our unique strategic positioning in the global tech landscape rather than simply launching ever more startups. European tech needs a fundamental rethinking of how we build, scale, and sustain globally competitive companies while keeping them rooted in Europe.

I believe this moment is an opportunity to revisit the critical topic of building in Europe. In this edition, which delves even deeper than usual, I'll synthesise my thoughts and writings on the subject. Consider this my contribution to the current discussion—a foundation for our collective efforts to chart Europe's path towards technological sovereignty and economic resilience 👇

1/ How far behind is Europe in building tech companies?

Europe isn't just behind in tech—it's falling further behind with each passing quarter while clinging to comforting myths about its potential.

The lagging position has become part of European tech's identity, with resignation baked into the ecosystem's culture. Yes, some investment firms maintain and execute on strong European theses—Saul Klein's New Palo Alto concept comes to mind from our 2020 conversation. These perspectives have merit. And yes, contrarians will cherry-pick statistics or adjust variables to paint a rosier picture, but these exercises in numerical gymnastics don't change the fundamental reality: Europe is lagging from virtually every meaningful metric.

Let's examine how Europe has consistently failed to build globally successful tech companies:

In 2024, not a single European tech company ranks in the global top 20 by market cap. US tech giants Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet each exceed $2T in value. Europe's largest tech company, ASML, stands at $279B. The entire European tech ecosystem is worth less than Apple alone.

European users overwhelmingly depend on non-European platforms. Meta's platforms, Google, and YouTube dominate European digital life. Many Europeans shop on Amazon. Spotify is the rare European exception in global platform rankings.

US tech companies invest more than twice what European firms do in R&D. The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard highlights this gap: “With €181.6B in 2023, the US software companies invested about 10 times more than their EU-based counterparts, while in 2013 this factor was only 5.8.”

Europe struggles to scale startups. In 2023, it created just seven new unicorns, compared to 14 in the US. Atomico's State of European Tech 2023 shows that European startups raise smaller rounds at every stage than their US counterparts.

These statistics paint a clear picture of systemic failure that isn't negated by rare, anecdotal exceptions like Spotify (€116B market cap) and Revolut (valued at $60B earlier this year—and profitable). Both these cases are instructive:

Revolut's European retention stems largely from the inherently local nature of financial services. Regulatory fragmentation creates friction when trying to serve the US market, but on the other hand it shields Revolut from direct competition with comparable US firms on its home soil.

Spotify is virtually the only evidence that a European tech giant with global ambitions, including in the US, can remain European, and even that was more accident than design. The company could have easily been American, but through Daniel Ek's determination, it wasn't.

2/ Why do imported playbooks fall short?

Given Europe's persistent inability to produce tech giants, the natural reaction has been to look abroad for successful models to emulate.

However, we’ve known for quite some time that Silicon Valley recipes don’t translate well in Europe: we don’t have the same ingredients, the kitchen isn’t organised the same way, and the cooks struggle to communicate due to cultural and language barriers. More specifically, we in Europe have fragmented markets (notably in terms of culture and language), diverse regulatory frameworks (despite the EU's Single Market), distributed talent pools, and a lack of sophistication and depth in European financial markets. Thus the challenge for those seeking to build in Europe is not about following the Silicon Valley recipe—it is about creating a new recipe, an entirely new approach that leverages Europe's unique strengths.

Those of us who have worked in European tech for more than a decade understand this well. When I joined this world back in 2010, everyone simply tried to apply the Silicon Valley playbook, promising to “disrupt” markets and trying to raise funds and build products with methods found in (US-centered) Venture Hacks and Getting Real. It did not deliver convincing results, to say the least. Yet we kept going, making only superficial adjustments, because the idea that another playbook was possible had not even crossed our minds.

Then, as alternative models emerged, the limitations of the Silicon Valley approach became clearer. To me, everything changed between 2014 and 2018, as Chinese tech companies rose to global prominence, starting with Alibaba's 2014 IPO and culminating in Sequoia's Michael Moritz's landmark op-ed about China in the Financial Times in January 2018. This watershed moment forced Europeans to acknowledge a new reality: alternative routes to building tech companies existed. Tech giants had emerged from a completely different context, using fundamentally different methods.

Indeed, the Chinese model diverged from Silicon Valley in several crucial ways:

China developed on a different timeline. While Silicon Valley evolved over eight decades with steady support from defence spending and academic institutions, China compressed this development into roughly two decades.

The government played a much larger role. Instead of the arm's-length relationship typical in the US, Chinese tech companies grew through active state participation and strategic industrial policy, both at the national and provincial levels.

Companies took a different approach to the market. As detailed by Kai-Fu Lee in his mindblowing AI Superpowers, Chinese firms adopted a “whatever works” mentality, often starting with simple copies but rapidly evolving unique business models suited to local conditions.

They built infrastructure from the ground up. Rather than relying on existing systems, Chinese tech companies often had to create entire infrastructural layers from scratch, leading to more vertically integrated businesses and the emergence of the "superapp" model.

This revealed something profound: Silicon Valley's model was not a universal template but merely one possible path. China's success demonstrated that entrepreneurial ecosystems could thrive by adapting to local conditions rather than replicating Silicon Valley's specific circumstances.

For Europe, the realisation that both the US and China excel at building tech companies, albeit with different playbooks, should be liberating. If two radically different paths to building tech companies exist, there is no reason why Europe cannot forge its own third way—one that leverages its unique advantages and circumstances rather than importing ill-fitting foreign models.

In other words, we need to acknowledge that company-building must be adapted to the local context—what Robyn Klingler-Vidra calls “contextual rationality.”

3/ What should we be building in Europe?

If both Silicon Valley and China have forged distinct paths to tech success based on their unique contexts, it follows that Europe must develop its own approach.

But before discussing how to build, we must first clarify what to build. In this edition, I'll mostly use the shortcuts “building”, or “building tech companies”, but the longer version is that our collective goal should be building profitable tech companies with a multinational footprint that happen to be headquartered in Europe. Every word matters in this category:

We should aim at building tech companies, by which I mean companies that operate within the techno-economic paradigm of the current Age of Computing and Networks. There's no need for the tech to be high, deep, or particularly innovative. What matters is that these 21st-century companies are the paradigmatic equivalent of those relying on mass production in the 20th century. In the last century, we in Europe succeeded in building car manufacturers, notably in Germany, France, Italy, and the Nordics. This century, we must seek to build tech companies.

Those companies need to end up being profitable, not only because “happiness is positive cash flow,” to quote the late venture capitalist Fred Adler, but also because profits are what ultimately make a European company contribute to Europe's economic development. It's not enough to raise money at high valuations without ever generating profits. Return on invested capital (ROIC—see a primer by Michael Mauboussin here) is the outcome of capitalism done right, and profits are the only sustainable way of generating such a return.

Those companies need to have a multinational footprint, meaning they must have a presence and serve customers at a very large scale, ideally beyond Europe and certainly beyond their home country1. That is how growing corporate giants contributes to local development. Those create and capture value at a global level, then realise this value by transforming it into wealth that is mostly local. Much like Daimler-Benz sells Mercedes cars everywhere in the world, enriching Germany in the process (well, sort of, under the right conditions).

Finally, those tech companies must be headquartered in Europe, which is crucial for capturing and retaining wealth locally. In today's digital economy, headquarters location determines where much of the value is ultimately realised. When tech companies are based elsewhere, Europe merely adds value to chains that enrich distant economies. This creates a troubling asymmetry: Europeans increasingly work and consume to enrich foreigners while European savings remain trapped in low-risk, low-growth local assets rather than flowing into building tech companies. Conversely, European-headquartered companies create a virtuous cycle where value captured globally returns to enrich the local ecosystem through dividends, capital gains, well-paid jobs, taxes, and accelerated money circulation. A tech company may operate globally, but it primarily enriches the region where strategic decisions are made and ownership is concentrated.

Success in building tech companies should be measured by Europe's ability to generate new, high-value firms. The goal is to maximise Europe's ROIC, wherein the value added by newly established companies (with profits as a proxy) increases more rapidly than the total amount of funds invested, including operating expenses and capital expenditures.

In other words, our version of ROIC should assess how efficiently Europe creates value from its investments in building tech companies—and we should expect this ROIC to increase over time as we strengthen Europe's strategic positioning.

4/ How can Europe find its strategic positioning?

Once we're clear on the goal (building profitable tech companies with multinational reach, headquartered in Europe) and our metric (ROIC), we can apply Michael E. Porter's strategic framework.

As Harvard's Porter outlined in his landmark 1996 Harvard Business Review article What Is Strategy? (which I commented here), strong strategic positioning includes these key aspects:

Europe's strategic positioning must start with Porter's core insight of a distinctive value chain: success comes from “preserving what is distinctive about a company” and “performing different activities from rivals, or performing similar activities in different ways.” For Europe, this means developing a unique value chain that turns our supposed weaknesses—fragmented markets, regulatory complexity, distributed talent, aversion to risk, deficient capital markets—into a sustainable competitive advantage for building tech companies and maximising ROIC in doing so.

Making this positioning work demands hard trade-offs. Not everything that succeeds in Silicon Valley or China will succeed here, and that's perfectly fine. We need to be honest about what doesn't work in the European context and stop trying to force-fit foreign models. Some opportunities will have to be deliberately passed up to excel at others. For instance, we don't do blitzscaling in Europe, therefore we don't want to raise those mega rounds only targeted at funding exponential growth for loss-making businesses.

The power of a good positioning comes from how its components fit together. Each element—from regulatory frameworks to funding mechanisms, from talent development to market access—needs to reinforce the others. This isn't about isolated improvements but about building a well-calibrated machine where each part amplifies the effectiveness of the whole.

Finally, Europe's positioning requires continuity of direction. Strategy isn't something you change every time a new trend emerges or when immediate results don't materialise. Europe needs to commit to its chosen path and give it time to bear fruit, even when faced with pressure to chase quick wins or copy whatever seems to be working elsewhere.

Another important aspect is that finding a good strategic positioning is different from improving what Porter calls “operational effectiveness” (my own writing on the difference here). Too often, European tech builders fall into the trap of operational effectiveness—trying to match Silicon Valley's practices through isolated fixes like improving founder culture, adjusting regulations, or reforming stock options. But as Porter argues, “competition based on operational effectiveness alone is mutually destructive, leading to wars of attrition that can be arrested only by limiting competition.” We can improve our stock option regimes all we want, employee equity will always be more attractive in the US than it is in Europe.

In fact, improved operational effectiveness often derives from good strategic positioning. In our case, I expect that once Europe discovers the right strategic positioning for building tech companies, many of today's perceived shortcomings will naturally resolve through market forces and resource reallocation. When strategic positioning leads to higher ROIC (our key metric from Section 3), capital will flow toward the opportunities represented by building even more tech companies. This influx of capital won't just sit idle—it will get deployed to solve operational challenges, bridge cultural gaps, fix legal issues, and build missing infrastructure. We've seen this dynamic play out in China's tech ecosystem, where proper strategic positioning drove capital influx that rapidly solved seemingly intractable problems in payments, logistics, and digital infrastructure.

The key insight is that resource constraints and cultural barriers aren't fixed obstacles but rather symptoms of suboptimal positioning. With proper positioning driving higher returns, we should expect market forces to organically direct resources toward solving these secondary challenges.

With this framework, Europe's strategic imperative becomes clear: we must develop a unique positioning that leverages our distinctive attributes rather than trying to copy approaches that succeeded elsewhere. Only by making difficult trade-offs and building a coherent, reinforcing system can we create a tech ecosystem that thrives on European terms.

5/ Should we focus on the early stage?

When tackling Europe's challenge in building tech giants, many focus on the early stage.

The logic goes: if Europe lacks major tech companies, founders must be going astray from day one, so fixing that should be the priority. There's also the important idea that founders know best, should form “startup communities” (as documented by Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway—see here), and only once they find a viable path should an “entrepreneurial ecosystem”—investors and other supporters—step in to help. In short, everything starts with founders, and the best strategy is to optimise their first steps.

The problem with this early-stage obsession is that after 15 years, Europe still lacks a systemic track record of building profitable, multinational tech companies (Spotify, Revolut, ASML and Adyen being rare exceptions). That means there's no proven model to reverse-engineer in a systemic manner.

Instead of refining a well-tested playbook, we're just sending more founders onto Omaha Beach, hoping some miraculously break through enemy fire to pave the way for others. But after 15 years of failed assaults, isn't it time for the high command to rethink its strategy?

The conceptual mismatch outlined in Section 2 becomes particularly problematic at the early stage. In the US, a well-established playbook has been perfected over generations, resulting in profitable tech giants like Intel, Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, and many more. This is why programmes like the Thiel Fellowship—providing subsidies for young people to build companies rather than pursue higher education—make perfect sense and yield results in the US: they fuel a well-oiled machine that reliably transforms ambitious founders into global tech powerhouses.

Europe, however, lacks that machine. And without our own proven playbook, early-stage interventions become premature optimisations of an unproven system. When I see systematic attempts to improve the early stage 15 years after we began trying, it reminds me of developing countries investing heavily in higher education but failing to create enough high-skilled jobs—leading to brain drain, unemployment, and unrest.

We should expect the same dynamic to apply to Europe's tech ecosystem: more startups fail; those that succeed scale by expanding—and eventually relocating—to the US; would-be founders opt for corporate jobs instead of risking their

lifecareer storming the beach; and Europe sinks further into slow growth, low productivity, and a widening gap in tech leadership.

But wait—you might ask—wasn't I the co-founder of a startup accelerator (The Family) that, from 2013 onward, aimed to do precisely this: improve the early stage systematically? This critique may seem surprising coming from someone with my background, but my experience with The Family taught me precisely why this approach is limited. Let me quote/paraphrase my 2020 essay on Y Combinator:

Y Combinator made a key difference in leveling up the Silicon Valley ecosystem, because turning early-stage investment into an industry is the finishing touch in polishing an ecosystem that works—and Y Combinator provided that finishing touch to Silicon Valley.

Early-stage investment firms, especially self-styled “accelerators”, are misleading for outside observers. We think they are the first brick to be laid out because those firms intervene at the start of business life. But in reality, it is exactly the opposite. Firms such as Y Combinator are rather the finishing touch to an already large and healthy ecosystem (in this case, Silicon Valley), in which we seek to optimise the first steps of the new generations who are following known steps.

In other words, “accelerators” only work well if they have something to pass on. At The Family we had our own doctrine to share, but nothing more. It was ours, not everyone adhered to it, the only thing is that we had worked hard on it, we believed in it, and we kept on refining it day after day. A healthy ecosystem like Silicon Valley has something to convey. But Paris, as an ecosystem, has nothing to transmit that is stable, unequivocal and proven, because it lacks earlier generations of widely successful tech companies.

Therefore it's impossible to reverse engineer what maximises the probability of success at the later stages if you don't have previous generations of companies that have been widely successful. Y Combinator could reverse engineer startup success in Silicon Valley. We in Europe can only guess what could eventually work and try and make it happen.

In short, all of these accelerators that you can find in every city in the world, often modelled after Y Combinator (even with misinterpretations), are like painting the inside of the house before you put the roof on. It's time to learn how to do it right and to realise that Y Combinator wouldn't exist without the healthy ecosystem that is Silicon Valley—and that it's useless, even counter-productive, to try and emulate it in the absence of such an ecosystem!

To be clear: it is still the job of any early-stage investor backing founders in Europe to support them in a relevant way—that is, allocating resources dynamically to help outstanding founders become independent of their local (and likely immature) entrepreneurial ecosystem.

However, I believe any collective effort that focuses too much on the early stage overlooks essential insights. One is that we lack enough success stories to systematically reverse-engineer what works and what doesn't at the early stage in Europe. The other is that we are far too deep into the shift to the Age of Computing and Networks to keep betting everything on early-stage founders.

As I wrote more than a year ago, The Door Is Closing on Startups, and we now know enough about the current techno-economic paradigm to take a more proactive approach—one that embraces a follower mindset when it comes to catching up with more advanced economies such as the US and China.

6/ What happens when the fog of computing and networks lifts?

Fifteen years ago, the startup landscape was still defined by widespread uncertainty—a dense fog obscuring both opportunities and dangers.

This fog served a crucial purpose: it deterred established companies, which had too much to lose to venture blindly into the unknown. Meanwhile, startups, with nothing to lose, could charge through this uncertainty. While many failed, those that survived found treasure on the other side and quickly built defences before incumbents could catch up.

Today, however, the fog has largely lifted from computing and networks. The path to digitising business is well-mapped, with clear playbooks and known pitfalls. Even AI, despite its revolutionary potential, has introduced surprisingly little uncertainty in its commercial development. When ChatGPT emerged, major tech companies didn't hesitate—they swiftly deployed their considerable resources to launch competing models. Just two years later, we already have cheap, mature open-source alternatives like DeepSeek. This rapid response suggests we are now operating in a landscape of known challenges tackled with production capital, rather than fundamental uncertainty addressed with risk capital.

This unprecedented clarity brings both challenges and opportunities for Europe:

Being first matters less. With less uncertainty, early movers no longer have the decisive edge they once did. Success now depends more on execution and scale than on pioneering in uncharted territory.

Resource allocation improves. Clearer visibility allows European companies to make more informed strategic choices about where to invest and compete—an advantage for a capital-deprived continent like Europe, and a good lever to pull for maximising ROIC.

Latecomers can catch up. A more predictable landscape enables those behind to learn from others' mistakes, refine their approach, and compete more effectively.

Defensibility becomes crucial. Without uncertainty as a natural barrier, European companies must develop other competitive advantages—whether through regulation, market position, or technical excellence.

At the scale of entire countries or regions, history repeatedly shows that followers often surpass initial leaders in economic development. Britain pioneered the Industrial Revolution, but Germany, France, and the US ultimately built more powerful industrial economies. The US led in mass automobile production, yet Germany, Japan, and South Korea later created some of the world's most successful car manufacturers. Each follower studied the leader's path, avoided their mistakes, and adapted their approach to their unique context.

Now we are in the Age of Computing and Networks, with the US blazing the trail and China as the first major follower. This presents Europe with a crucial opportunity—but it requires embracing an uncomfortable truth: in the current era, and for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, Europe is effectively a developing region from the tech perspective.

This isn't merely a provocative statement—it's a strategic reframing that could unlock new possibilities. Just as 19th-century America saw itself as developing and protected its infant industries accordingly, Europe needs a similar mindset shift to capitalise on the advantages of being a follower in a landscape where the fog has lifted. Accepting this developing status would justify industrial policies that might otherwise seem inappropriate for 'advanced' economies: protecting infant industries, making long-term state investments in technological capabilities, and implementing policies that prioritise tech sovereignty over short-term market efficiency.

The advantages of this follower position are substantial: infrastructure is cheaper to build (as costs have declined over time), talent pools are deeper (as technical education has become more widespread), and market opportunities are clearer (as pioneers have already validated business models). Europe's distinct attributes—its regulatory framework, industrial base, and market characteristics—aren't obstacles but potential assets in building a unique approach to tech success. The question isn't whether Europe can compete—history proves that followers can catch up with leaders—but whether we are ready to embrace our position as a developing economy and play the long game, as South Korea did with Samsung and Hyundai, Japan with its post-war transformation into a leader in robotics and advanced manufacturing, or Mainland China did from 1978 onward thanks to Deng Xiaoping.

(Note that following is different from imitating: In the 20th Century, Japan followed the US in car manufacturing, but Toyota took a completely different approach from the Big Three in Detroit.)

For Europe, this isn't about admitting defeat—it's about choosing the right strategy for our actual position. When a region is still developing, it can justify protecting infant industries, investing heavily in fundamental capabilities, and making bold, proactive moves that might seem inappropriate for a ‘developed’ economy. For a follower, what to do is clear—how to do it is where the real challenge lies.

Europe is fully capable of competing globally in tech, but success depends on acknowledging our true starting position and charting an effective path forward. Instead of trying to pioneer, we must focus on leveraging the advantages of following—because by now, most of the pioneering opportunities have been exhausted anyway.

7/ How does Europe's regional dynamism drive its tech future?

Having identified what Europe needs to build and established that we require a unique strategic positioning, we face a fundamental question: who should orchestrate this economic transformation?

This question goes beyond simply identifying specific individuals or institutions—it reveals a deeper tension between centralised and decentralised approaches to economic development.

Historically, economies that successfully orchestrated rapid development—such as Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew or South Korea under Park Chung Hee—relied on strong central leadership and dirigist industrial policies. Europe, however, lacks both the institutional framework and the collective mindset for such an approach.

Indeed, many mistakenly view Europe as a monolithic entity simply because of the European Union. But the EU is not a unified economic system with a single chain of command. If Europe embraced its status as a developing region in tech (as argued in Section 6), a strong central authority might naturally emerge to drive this development. But at present, Europe’s largest economies continue to see themselves as advanced nations—committed to preserving open societies, free enterprise, free movement, and, crucially, relatively weak central governance. Meanwhile, the regions forming “Dynamic Europe”—to borrow a term from the venture capital firm Bek Ventures—actively resist centralisation, knowing that any overarching structure would likely be controlled by the slower-moving Western European economies.

Given this reality, Europe's tech renaissance must be decentralised—driven not by Brussels or national governments but by founders, investors, and market forces. Progress won't come from a grand continental agenda but from collective action across Europe's diverse and distributed entrepreneurial ecosystem.

A decentralised approach is all the more necessary because regional dynamism is Europe's hidden asset. While productivity data often paints a grim picture of the continent's overall performance, countries like Poland and Bulgaria continue to show growth, while larger economies such as the UK, France, and Germany have stagnated. These “Dynamic Europe” regions have the potential to lead Europe's tech future precisely because they aren't burdened by the mindset of being ‘advanced economies.’

What makes this “Dynamic Europe” distinct isn't just geography; it's a particular mindset and approach. As Bek Ventures defines it, this encompasses Central and Eastern European founders who are “hardworking, technically talented, and ambitious with global scale a non-negotiable imperative.” These founders approach company-building with fewer preconceptions about what's possible, less attachment to legacy systems, and a natural orientation toward global markets from day one—precisely because their home markets often lack the size to support unicorn-scale ambitions.

This mindset creates a powerful advantage. While Western European founders might start by optimising for their home market and often end up being trapped in it, Dynamic Europe founders begin with global ambitions by necessity. Companies like UiPath (Romania), Pipedrive (Estonia), Wise (Estonia), and Infobip (Croatia) exemplify this approach—building globally competitive products from regions traditionally overlooked by mainstream tech investors, yet achieving valuations that eclipse most Western European startups.

Much like China in the 1990s, Europe is often misjudged when viewed as a bloc. Investors who then saw China as a homogeneous entity overlooked the transformative growth in tier-1 cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing—and later, tier-2 cities like Chongqing, Chengdu, and Hangzhou (home to Alibaba, no less). Similarly, seeing Europe only through the lens of its stagnating legacy economies obscures the bright spots of innovation and expansion.

8/ How can we align without central control?

The challenge, then, is to achieve Lee Kuan Yew-style outcomes without Lee Kuan Yew himself—or the competent, central bureaucracy he had at his disposal in Singapore. A decentralised approach requires different mechanisms to align efforts and foster strategic coherence.

Compelling narratives, for instance, inspire action and create shared understanding. Several years ago, I wrote about the need for more European stories and took part in various initiatives to bridge that gap. Since then, much progress has been made—the growth of the pan-European media that is Sifted or Pia Michel's impressive reporting on her Grand Tour of Europe are just some examples.

These narratives aren't merely inspirational stories—they function as powerful coordination tools in several concrete ways:

First, effective narratives help shape investment theses. When Atomico published The State of European Tech reports starting in 2015, they didn't just document the ecosystem; they created a framework that influenced how capital was allocated. By highlighting success patterns in specific regions and sectors, these narratives directed investors' attention and capital toward promising opportunities that might otherwise have been overlooked.

Second, narratives establish shared identity and purpose. The 'French Tech' initiative, launched in 2013, created a recognisable brand and rallying point that unified previously disconnected entrepreneurial communities. This wasn't just symbolism—it led to measurable increases in talent retention, international recruitment, and eventually policy reforms that might not have happened without this collective identity.

Third, narratives signal opportunity to talent. When Daniel Ek describes Spotify's mission as “giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art,” it's not just company rhetoric—it's a beacon that attracts specific types of talent to Stockholm, creating cluster effects that benefit the entire ecosystem. Similarly, when DeepMind positioned London as a centre for ethical AI development, it sparked a migration of researchers and startups focused on responsible technology.

But narratives are not the only tool to coordinate efforts in decentralised systems:

Practical theories help economic actors make better decisions. Some assume that building tech companies leaves no room for abstract thinking, but that's a mistake. Andy Grove, the legendary Intel CEO, was a devoted student of Clay Christensen's The Innovator's Dilemma. He even mandated that Intel's managers be trained in Christensen's theories, seeing them as a strategic and managerial lever: “A common language and a common way to frame the problem so that we can reach consensus around a counter-intuitive course of action.”

Speculative bubbles, despite their excesses, often direct capital toward emerging opportunities. As Carlota Perez, my mentor Bill Janeway, and more recently Byrne Hobart of The Diff have argued, bubbles create urgency. Investors who believe the future will be radically different from the present feel compelled to act—either because they think it won't happen unless they build it, or because they fear someone else will build it incorrectly.

All in all, economic development tends to follow a predictable sequence which accommodates a decentralised approach. For Europe, that means:

A shift in perspective—Entrepreneurs, investors, and institutions must start acting as though they are operating in a developing economy with high growth potential. Coordination mechanisms such as narratives and theories can help achieve this.

Strategic positioning through decentralised action—As capital and talent flow toward high-value opportunities, specialisation emerges. In hindsight, this pattern may resemble a deliberate strategy, but in reality, it will be the product of many independent choices.

Iteration over central planning—As the system evolves, inefficiencies are corrected, coordination improves, and competitive clusters strengthen—leading to a self-reinforcing cycle of economic upgrading.

In sum, without a European Lee Kuan Yew or Park Chung Hee to direct resources, we have no other choice: our European strategic positioning must be discovered through decentralised coordination. The ultimate measure of success remains ROIC—our previously established metric for how effectively Europe converts building tech companies into wealth creation, purchasing power, and economic security. The question isn't who should be in charge—it's how we create the conditions for a decentralised renaissance where no one needs to be in charge at all.

9/ Can we draw inspiration from the Rothschild banking dynasty?

The challenge of building a pan-European entrepreneurial ecosystem without centralised authority has historical precedent.

In the 19th century, despite lacking supranational governance structures, Europe maintained a functioning economic system driving global growth and innovation. At its heart was what Karl Polanyi called “haute finance”—a network of banking families creating international financial infrastructure that transcended national boundaries.

The Rothschild banking dynasty exemplifies this approach. Mayer Amschel Rothschild built a financial empire by strategically placing his five sons in key European financial centres: Frankfurt, Vienna, London, Naples, and Paris. This distributed family network created something remarkable: a pan-European financial system operating beyond national interests. As Polanyi noted,

The Rothschilds were subject to no one government; as a family they embodied the abstract principle of internationalism... their credit had become the only supranational link between political government and industrial effort.

What's striking is how this functioned without central authority. Each Rothschild brother maintained local autonomy while participating in a shared enterprise with common protocols, communication systems, and values. As documented in Niall Ferguson’s masterful history of the dynasty, The House of Rothschild, they developed sophisticated courier networks and coded messages to transfer money and intelligence faster than competitors or governments, allowing them to make sound investment decisions across all of Europe, and to shape continental development for generations.

Today's European tech ecosystem faces similar fragmentation challenges. French tech rarely interacts with German tech; Spanish tech operates separately from Dutch tech. This isolation is reinforced by the media celebrating local heroes and by investors (and governments) prioritising national champions.

The Rothschild model suggests an alternative: decentralised but coordinated networks leveraging local knowledge while maintaining a multi-national perspective. Some of today's successful European founders already follow this pattern. Daniel Dines of UiPath worked at Microsoft in the US before returning to Romania to build his company—exemplifying what AnnaLee Saxenian calls “brain circulation,” where entrepreneurs gain experience abroad but return to build companies at home.

The key insight is that successful European tech companies always have a local dimension—you can't understand Spotify without understanding Stockholm, just like in the 20th century you couldn’t understand Michelin without understanding Clermont-Ferrand, France—but they must transcend locality to operate at continental and global scales.

The lesson isn't that we need new banking dynasties (the world today is far removed from the 19th century), but rather institutional innovations creating continental-scale coordination without requiring continental-scale authority. In a founder and financier-led tech ecosystem, these coordination mechanisms will likely emerge from the private sector rather than from Brussels, Paris, or Berlin, contributing to Europe's strategic positioning for building tech companies.

10/ How can Europe's unique features become an advantage?

Europe's fragmented market has long been cited as a primary obstacle to building tech companies at scale. Unlike the US market's relative homogeneity, European entrepreneurs face a patchwork of different languages, regulations, and business customs that make continental expansion challenging. This fragmentation creates friction that prevents most startups from achieving the scale necessary to compete globally. But what if this very complexity could become Europe's advantage?

Remedying Fragmentation Through Buy-to-Build

One promising approach is the “buy-to-build” strategy, a rather traditional play in the private equity world. Instead of the traditional venture-backed approach of organic growth across borders (which is very hard to achieve, as I can testify based on The Family’s portfolio or well-known examples such as Doctolib and Malt), European tech companies can consolidate through private equity-funded acquisition, bringing together similar solutions from different markets under one roof.

As founder Lucas Bédout aptly noted on LinkedIn:

The European market is fragmented, with tons of country-specific solutions offering similar feature sets that are never consolidating because no one can afford to buy the others. Look how many companies based in different countries are solving the exact same problem right now in Spend Management, Procurement, Billing, Treasury, SMB payments...

There are meaningful precedents showing this approach can work. What Trainline achieved with KKR's backing—acquiring its competitors across Europe, including the Paris-based Captain Train—offered an early playbook. Klarna has pursued a similar strategy in fintech, acquiring companies like Sofort in Germany and BillPay to consolidate its position across Europe's fragmented payment landscape. Adevinta, the Norwegian classifieds group, expanded pan-European operations by acquiring eBay Classifieds Group for $9.2 billion, uniting various marketplace platforms like Mobile.de in Germany and Leboncoin in France. Similarly, TeamViewer built its remote work solutions business by strategically acquiring companies like Ubimax and Austrian firm Xaleon/Chatvisor.

However, to my knowledge, this has not yet led to the emergence of a dedicated segment within European private equity focused specifically on cross-border tech consolidation.

That said, PE-backed buy-to-build cross-border investments seem to be the future for Europe. This strategy recognises that Europe doesn't need more early-stage startups; it needs fewer, but stronger, well-capitalised multinational companies that can compete at continental scale, on par with their US counterparts.

By acquiring similar businesses across multiple European countries, companies can swiftly secure the market coverage necessary to take on American rivals. This consolidation not only reduces the inefficiency of competing national champions but also creates larger entities capable of making significant investments in product development and talent.

Leaning into Europe's Complexity

Tom Lambert of LocalGlobe offers another perspective: Europe's complexity isn't just a challenge to overcome—it's a potential source of competitive advantage:

Europe isn't simple to operate in. It's a patchwork of markets, regulations, currencies, payment methods, and cultures. This complexity creates friction that many view as challenging. But it's precisely this complexity that birthed companies like Revolut, Adyen, and Wise.

Companies that master Europe's complexity develop capabilities that are difficult for outsiders to replicate. They build deep expertise in navigating regulatory environments, localising products, and managing across cultures—skills that become moats protecting their businesses from both American tech giants and new entrants.

AI as Europe's Integration Catalyst

Artificial intelligence may prove to be the great equaliser that helps European tech overcome its fragmentation challenges. As AI advances, particularly large language models, many of the barriers that have historically made cross-border expansion difficult are becoming less significant:

Advanced AI translation technology is breaking down communication barriers by dramatically reducing the cost and complexity of adapting products for different European markets.

Emerging compliance-focused AI solutions are making regulatory navigation simpler, as software becomes powerful enough to implement complex compliance requirements directly into applications.

New data extraction capabilities are solving integration challenges with legacy systems, enabling European companies to modernise without the need for complete replacements of existing infrastructure.

This technological shift creates an opportunity for European tech companies to leapfrog the traditional SaaS model and build AI-native solutions that work within Europe's complexity rather than fighting against it.

Value Chain Integration

The future of European tech may also lie in deeper integration across value chains. Just as Japan's keiretsu system enabled Toyota's lean production revolution, AI's potential can only be fully realised through collaboration across companies, as I argued in my Who Will Be the Japan of the AI Era?

Rather than pursuing the traditional venture capital path of building independent companies, many European startups may thrive by forming deep partnerships with established enterprises. These collaborations would provide startups with not just funding but also data, domain expertise, and market access, while giving larger companies access to cutting-edge AI capabilities.

All in all, the approaches mentioned above acknowledge a simple truth: Europe's path to tech success doesn't need to mirror Silicon Valley's. By embracing our unique challenges and turning them into advantages, European tech can chart its own course to global competitiveness.

The powerful feedback loop is clear: more successful continental companies lead to better strategic positioning, which in turn creates more opportunities for success. The question is whether Europe's tech ecosystem is ready to embrace these alternative paths forward.

11/ How can we chart Europe's unique path forward?

We've spent time diagnosing Europe's tech challenges—fragmented markets, capital constraints, talent distribution, and the shadow of Silicon Valley's success. Now it's time to chart a pragmatic path forward that leverages Europe's distinctive attributes rather than attempting to replicate others' formulas.

This path forward doesn't mean starting from the early stage. Europe doesn't need more accelerators or seed funding—these are finishing touches for entrepreneurial ecosystems that already work, not foundations for ones still finding their footing. Instead, we need to expand the pool of successful tech companies with multinational footprints, using their examples to refine a distinctly European strategy.

The challenge isn't fixing what's broken, but creating something exceptional that works with our unique context. This requires what engineers call “impedance matching”—ensuring that all parts of our tech ecosystem work harmoniously together, minimising inefficiencies and maximising value creation. Consider how this impedance matching might work across different dimensions in Europe:

Market Integration: Rather than fighting against market fragmentation, use buy-to-build strategies to consolidate similar solutions across borders, creating continental-scale businesses that can compete globally.

Capital Deployment: Focus investment on scaling companies that have proven their ability to navigate European complexity, rather than spreading capital thinly across thousands of early-stage ventures trapped within their domestic market and unlikely to reach escape velocity.

Talent Development: Create pathways for AnnaLee Saxenian’s “brain circulation” rather than fighting brain drain, encouraging Europeans to gain global experience before returning to build companies at home, in the spirit of Jiang Zemin’s Go Out policy in 1990s Mainland China. This, I believe, requires a proactive approach toward European diasporas not only across the continent, but also in the US, Asia and elsewhere.

Regulatory Framework: Transform Europe's regulatory environment from a liability into an asset by developing technologies that make compliance easier, creating transferable advantages when entering other regulated markets globally.

Industrial Base: Leverage Europe's strong manufacturing heritage as AI and computational systems increasingly merge with the physical world, creating opportunities at the intersection of traditional industry and digital technology.

The end goal should be to grow an entrepreneurial ecosystem that resembles Formula 1: a high-tech domain of extreme diversity where most people speak imperfect English yet work together seamlessly. Formula 1 maintains a global footprint while remaining rooted in Europe, centred around Motorsport Valley in England yet making room for geographic diversity with Ferrari in Italy, Sauber in Switzerland, and Alpine in France (albeit not for long).

This analogy offers several instructive parallels for Europe's tech ecosystem:

First, F1 demonstrates how specialised technical excellence can thrive in Europe despite American dominance in many other sports and entertainment categories. While the US has NASCAR and IndyCar, Formula 1 remains distinctively European in its DNA yet globally successful—precisely the position European tech should aspire to occupy.

Second, F1's talent model is worth emulating: engineers, mechanics, strategists, and drivers from across Europe converge in multinational teams, communicating in non-native English that prioritises effectiveness over perfection. This practical approach to collaboration overcomes the language barriers that often fragment European tech efforts.

Third, F1's ‘coopetition’ model balances fierce competition with necessary collaboration. Teams compete intensely on race day yet work together on regulations, safety standards, and promotion of the sport as a whole. Similarly, European tech needs both healthy internal competition and coordination on issues like regulation, talent development, and global positioning.

Finally, F1 demonstrates how a highly technical, innovation-driven ecosystem can create value across the continent through a balanced governance model. The sport operates under a dual authority structure—the commercial rights holder (Formula One Group, owned by Liberty Media) and the regulatory body (FIA, headquartered in France)—that provides clear rules and commercial framework while still allowing teams to innovate and compete distinctively. This governance structure, combining centralised direction with team autonomy, offers a potential model for European tech: common standards and strategic alignment at the continental level, with execution and innovation happening within national and regional contexts.

I didn't choose this example by chance. While football (soccer) is as European and international as Formula 1, F1 stands out as a distinctly high-tech sport, proving that Europe can achieve global-scale excellence not just in marketing an appealing product worldwide, but also in mastering advanced technological fields.

Unlike F1, however, I don’t believe the vision laid out for European Tech in this edition requires much centralised command—which, in Europe, will never exist anyway. Instead, it needs founders who think beyond national borders from day one, investors willing to back ambitious cross-border consolidation plays, notably at the late stage, and a collective mindset that views Europe's complexity as a competitive advantage rather than a liability.

The journey won't be easy or quick. It took decades for Germany to outpace Britain in industrial production during the Second Industrial Revolution. It took generations for the US to build its technological dominance. But with clear-eyed strategic positioning and committed execution, Europe can forge its own path to global tech competitiveness—not by copying Silicon Valley, but by writing its own distinct chapter in the ongoing story of technological progress.

In conclusion, Europe doesn't need another accelerator or early-stage fund. It needs bold, long-term vision executed through concrete, practical steps that leverage our unique context rather than fighting against it. This is our challenge, and our opportunity.

Sign up to Drift Signal if you don’t want to miss the next issues 🤗

From Paris, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas

While Spotify and Revolut are often cited as European success stories with a global footprint, other examples deserve attention. ASML, the Dutch semiconductor equipment manufacturer, has achieved global dominance in its niche, supplying critical lithography machines to chipmakers worldwide while maintaining its European headquarters and R&D base. Similarly, Adyen, the Dutch payment platform, has built a truly multinational business serving major global clients while remaining firmly European in its governance and culture. These companies exemplify what we should aim for: profitable tech companies with global reach that generate substantial wealth within the European ecosystem.

Thanks Nicolas. A really good piece. I agree that Europe needs to use its landscape to position itself better. We will always be decentralised and speak multiple languages.

But we also have a huge population that lives close to one another and can consume and create great wealth. I think the PE play is a good one to start but it won't go far enough. We need to create companies of 500B (new word Frillion) in Europe and that won't come from PE.

We need to use our industrial past and information age "present" information to build a vertical integrated led future. We must be determined to scale companies to that size and value that serve Europe (and other markets) and solve Humanity Level Problems.

PS: I could not agree more on accelerators being the last brick you lay down when building an ecosystem!